How can teams handle the Ambiguity Curve?

Surfacing ambiguity early can help future decision making and moonshot choices

The future is riddled with ambiguity. Although business leaders, startup teams, and economic analysts may make educated guesses about what happens next, the outlook remains cloudy.

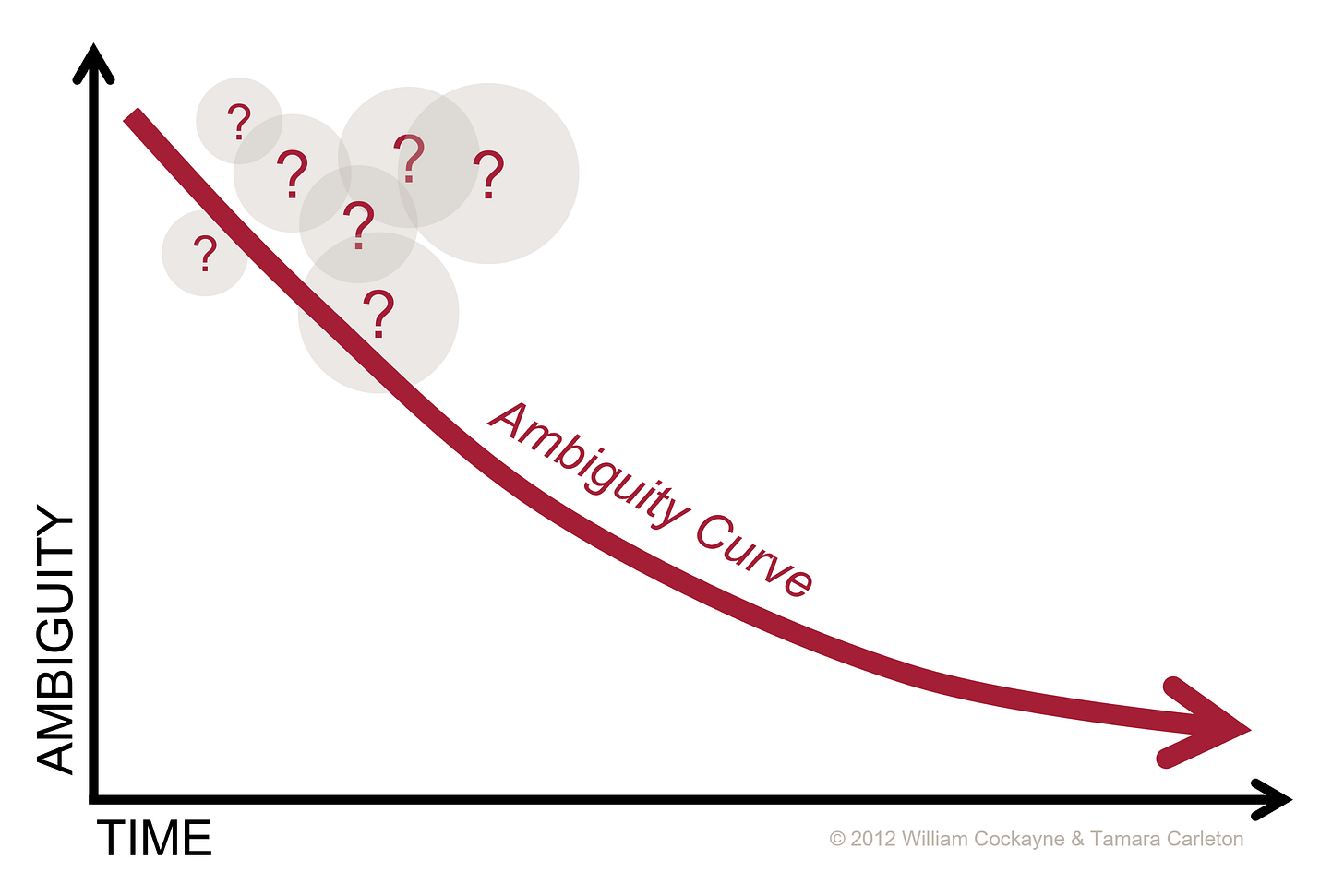

About 15 years ago, we described this basic phenomenon with an Ambiguity Curve. Simply, when you start a new effort – such as a first-time business, a moonshot endeavor, or even a family – the earliest stages have the most questions. This early time is fraught with many open variables and unknowns. Often, you don’t even know what questions to ask, let alone know how to go about finding answers.

In our original 2010 model, the x-axis shows time starting from an initial concept progressing to later stages, and the corresponding y-axis shows ambiguity rising from none to high. When teams start, their ambiguity level is in the high zone – feeling almost infinite when faced with a completely novel opportunity – which is shown in the top left of our diagram.

Tamara likes this version of our diagram because it captures that starting intensity and wonderful chaos. Many teams recognize they often start a new opportunity or project with many different questions. As they learn more about their opportunity space and learn to ask more and better questions, through activities such as early user tests, they gain more information and more answers, and their ambiguity level steadily drops along the Ambiguity Curve. However, their ambiguity level never fully zeroes out because there’s always something the team doesn’t know is missing. (Examples would be “how will the market respond after we launch?” and “what new opportunities might emerge when our solutions change a customer’s behavior forever?”)

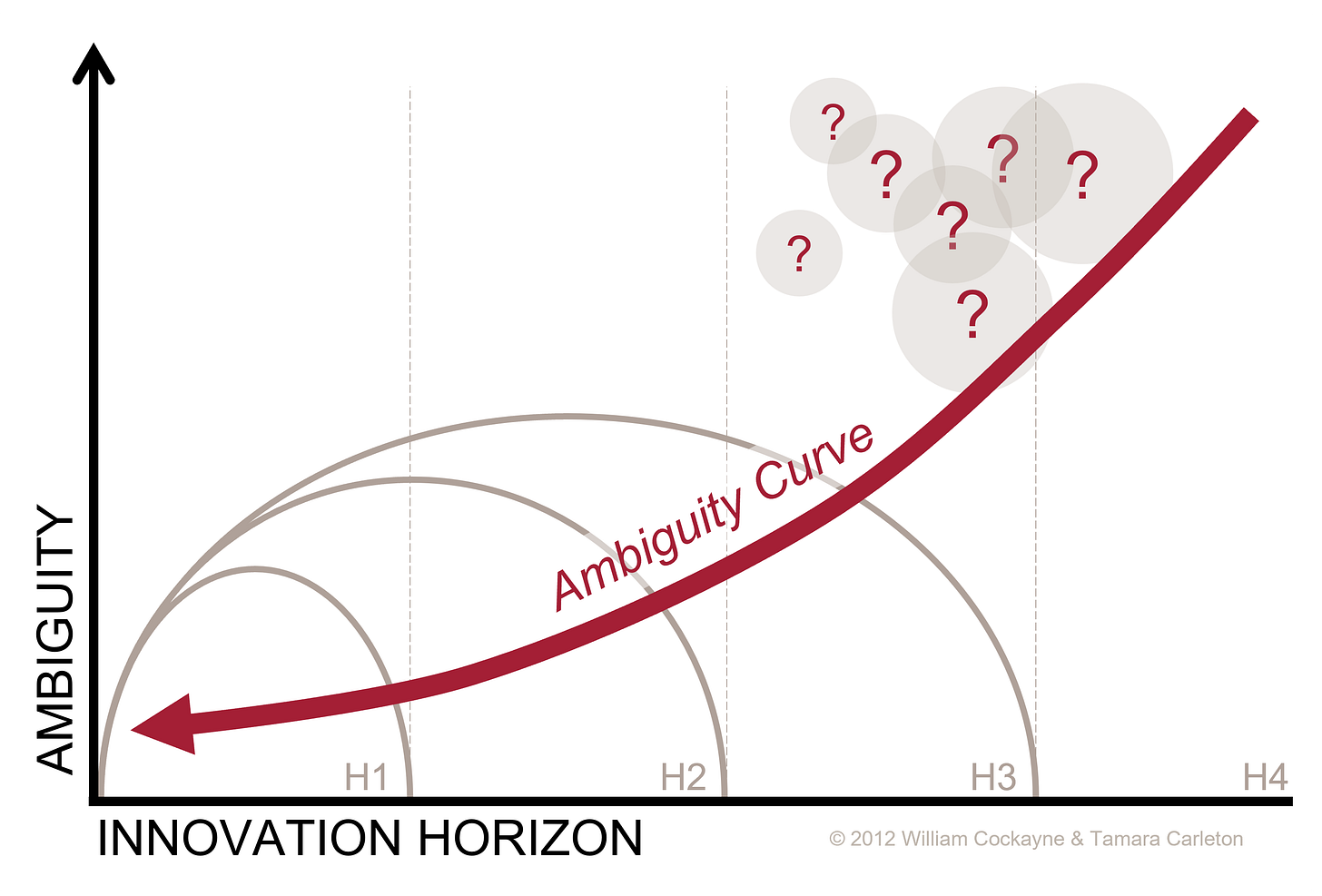

Bill prefers to swap the Ambiguity Curve, overlaid instead on our Four Horizons model. Same experience for an innovation team, though this version shows the ambiguity is highest during Horizon 4 (H4) – a time of imagination and envisioning – shown at the top right. On the other end at Horizon 1 (H1), business procedures and team activities tend to have far lower ambiguity, which is where you find quality checks and other standards in place that ensure all open questions have been properly addressed and there are no surprises.

The meaning of ambiguity

The concept of ambiguity is, in a circular manner, hard to define. We have heard that some languages, like Swedish, do not even have an exact translation of ambiguity.

Informally, humans say that something is “ambiguous” when it seems vague and unclear. In everyday life, you experience ambiguity when you hear that your medical test is “inconclusive”. Or, as you imagine a major career change, you can’t clearly see what that life would look like compared to your current familiar setup. These situations are not simple uncertainties, where you can recognize and compare clear options, such as “what drink do I want with lunch today?” Instead, you are faced with no obvious options, or you have no personal knowledge or experience of the range of possible choices, so therefore you have little to base your decision upon. Sometimes, you don’t even know if there are options to choose from or even if there is a decision to make, such as “is dropping out of college even an option for me?”

Of course, our visualization isn’t the first attempt to make teams aware of ambiguity. The most infamous model is the unknown unknowns, shortened to unk-unks, which are the factors that a team doesn’t realize that they don’t know so they cannot fully anticipate them. This model is often presented in a 2x2 matrix with (stay with us here!) known knowns, known unknowns, unknown knowns, and unknown unknowns.

There is also the Johari window, a classic psychology framework from the mid-1950s. This framework describes blind spots as behaviors, feelings, or motivations that are known to others but not known to you (for example, a personal habit of avoiding difficult conversations that then affects team dynamics). A way to address blind spots is to seek feedback. In this model, unknown areas are aspects of yourself that are unknown both to others and to yourself, which creates extra ambiguity. The response in this case is to find fresh challenges that can help reveal new abilities or unleash new potential.

These types of models are meant to bring the topic of ambiguity to the forefront of decision making for a leader or team. Especially in innovation, a probing question is “what questions aren’t we able to ask today that could come back to haunt us later?”

Using our Ambiguity Curve model in real life

When we developed our model of the Ambiguity Curve, we placed time on the x-axis to help teams recognize, even embrace, that early zone of ambiguity. They can’t know all the questions that they will need to ask across their coming journey – and certainly not at the starting line.

Building moonshots begins with wildly high levels of ambiguity. A moonshot, by definition, has no precedent or clear examples to follow. It typically is the first time for that bold and highly ambitious goal, not just for that organization but typically in the world. As such, moonshot teams naturally spend more time in the high ambiguity zone, and team members need to remain energized despite this dive into the unknown. This is also a time of active imagination, where teams can literally stare into the clouds as they ask “more questions that we have whiteboards,” as Bill likes to say.

Where do you personally sit on the Ambiguity Curve? When Tamara asks groups to reflect on their personal comfort zone, most people tend to vote in the middle zone. This is totally normal and very human. Few people thrive in constant high ambiguity, nor do most people like the extreme opposite of complete predictability either.

She then asks where they would place the people they oversee or work with on the Ambiguity Curve. This secondary group is often placed lower on the curve, and this rings true for most organizations. Many managers help translate broad goals or loose plans from senior management for their direct reports. These managers create safe spaces for team members, where questions can be raised and addressed. Ambiguity is removed constructively and often collaboratively.

Moreover, you can recognize the leaders in a group because they step up as role models, helping those around them to navigate ambiguity – often during chaotic periods such as business transformation, corporate reorganization, and financial crises. Certain roles are useful here. For example, forward-looking investors and advisors can help junior teams and those facing their own version of unk-unks to consider more questions and realize what options are available.

We also want to support those in an organization who flourish in low ambiguity zones, such as those handling safety procedures, where they limit surprises and remove doubt.

For moonshot teams, the high ambiguity zone can be a giddy period of question seeking. As they explore and compare possible future scenarios, chase their curiosity, become extreme collaborators and communicators, and build experiments, they will slowly determine the questions that matter. And with each question, what the options and decisions could, and even should, be. We urge these teams to poke at the questions raised, challenging all assumptions – including those from experts, naysayers, and earlier pioneers who may mean well. This approach will empower the team to move down the Ambiguity Curve, paving the way for others to follow.

How could you imagine bringing the Ambiguity Curve into your work practices? We would love to hear from you!

Reach us any time at hello@buildingmoonshots.com. (Tamara reads every email.)

GET THE SOURCE

🚀Get your copy of Building Moonshots

Building Moonshots is your handbook for the almost impossible, describing over fifty ways for building big ideas with big impact. Financial Times describes this book as “easily digestible” with “practical insights for extraordinary entrepreneurship”.

SPECIAL BOOK BONUS

💫 Download your free poster of all 50+ Moonshot Ways

Download a free poster showing all 50+ Moonshot Ways that you can display as personal inspiration, team reminder, or cultural invective.

(print it big on US 11x17 or A3 sized paper)

OLDIE BUT GOODIE

📘Download your free copy of the seminal Foresight Playbook

If you haven’t yet, also download your free copy of the playbook that started it all: our Playbook for Strategic Foresight and Innovation. Developed from the first decade of courses, research, and insights from Stanford’s University Foresight program, and generously sponsored by the government of Finland’s innovation agency, these foresight tools and mindsets are easy to adopt, quick to apply, and used in thousands of the world’s leading innovation-seeking organizations. (Look for new playbooklets later in 2024!)